How building muscle works

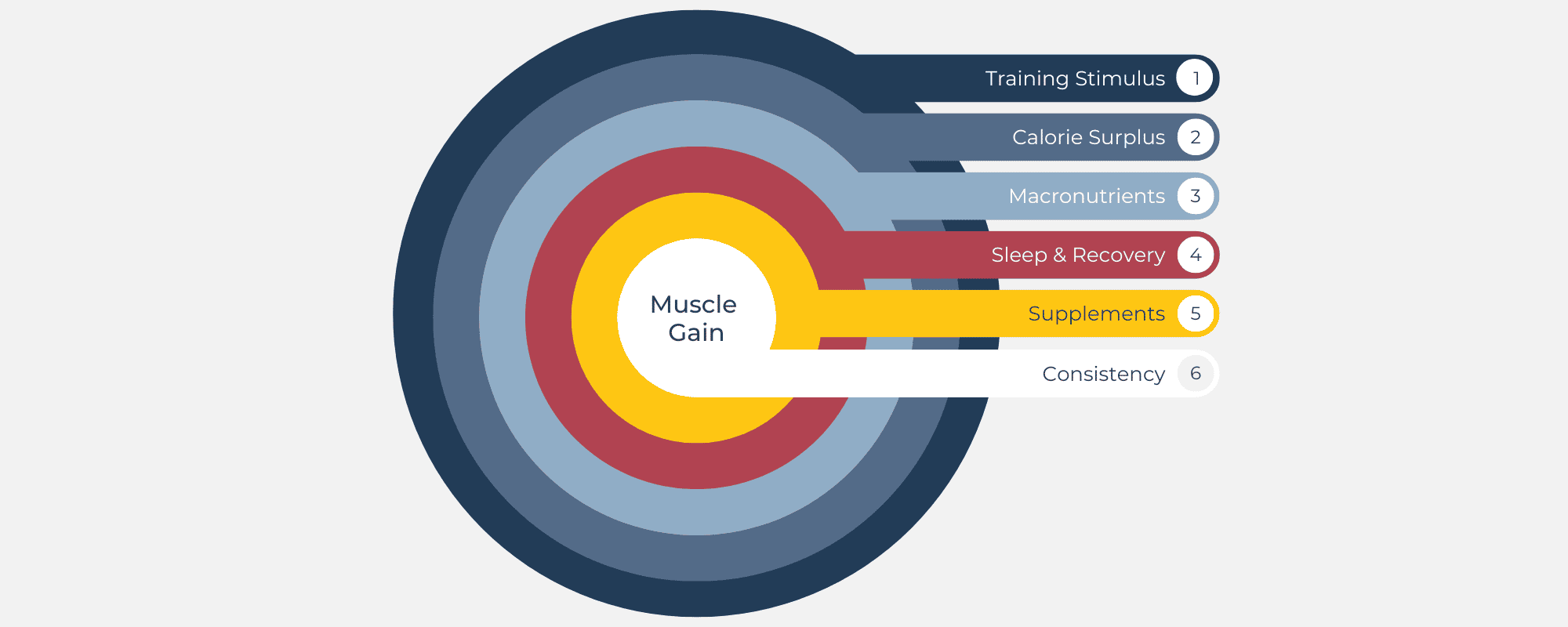

Muscle gain, commonly referred to as hypertrophy, is the development of mass, density, shape and function of muscle cells. For muscle gain to occur, it requires both exercise stimulus and the correct nutrition strategy to suit your individual needs. It is not any exercise that will stimulate it however, building muscle requires consistent and progressive resistance training in order to stimulate muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and build muscle in response to exercise. The MPS response is further supported by our nutritional intake if we are in an anabolic state (calorie surplus), meeting our macronutrient requirements and consuming nutrient dense foods. To learn more about the intricacies of muscle gain and anabolism, visit this article – The Key Elements for Building Lean Mass – daveynutrition.

We support your goal, but do you?

Do you know why you are targeting muscle gain? It is important that you know your why, because it is not going to be an easy road. Building muscle is difficult, but I assure you that it is a goal worth chasing! It requires consistent effort each week, and time for training, preparation, recovery, and planning.

From a performance perspective, improvements in lean muscle mass can be linked to key sporting physical indicators such as strength, power to weight ratio and sprint times etc. However, whether or not an athlete should target muscle gain should be determined on an individual basis and factors such as the time of season, individual sport demands and past body-composition history should be considered. It would be advisable to consult a performance nutritionist and work with an experienced coach to ensure you have the correct exercise programme to reach your goal.

From a health perspective, advancing age is associated with a loss of muscle mass, also known as sarcopenia. Therefore, preserving or increasing lean muscle mass would be an important goal to improve life quality and mobility. Check out this video where Brendan Egan explains this concept really well. From a subjective perspective, a key season people do target muscle gain is for subjective visual improvements to their body shape, tone and appearance.

Can building muscle burn fat?

Muscle gain and fat loss are two very different processes. If you haven’t already read this article, I encourage you to do so before going any further – The Key Elements for Building Lean Mass. The most effective rates of muscle development require a calorie surplus. However you can build muscle in a calorie balance and untrained individuals can even build muscle in a calorie deficit with adequate protein intake.

For muscle gain to occur, new tissue is being built, the body is being put under stress to lift heavier weights and do more work, muscle fibres are broken down and the body must work to repair them while also building new proteins – which over time will lead to bigger, stronger muscles. It requires the body to be in an anabolic state. Anabolism (hypertrophy) results from initial breakdown processes (catabolism), which transitions to the growth of new tissue (anabolism) in the presence of sufficient energy and nutrients. Whereas fat loss will require a calorie deficit, meaning that you are expending more calories (energy) than you are consuming. Read more on Fat Loss in our 3 part series on solving the fat loss puzzle: how to lose fat in a healthy, sustainable manner: Part 1 & Part 2 & Part 3.

As you have probably realised, these processes and goals are very different. Building muscle is a much slower process than losing fat mass. Depending on where a person is starting from, it can take up to 6 weeks to build 1 kg of lean mass, whereas 2 kg of fat mass can be lost in approximately 4 weeks. For overweight & undertrained (newbies), these are easier to achieve and can be achieved simultaneously.

Although the process of achieving those goals can be similar such as having a consistent sleep routine, consistent meal patterns, hitting your protein intake, managing stress and keeping yourself well hydrated, the calorie balance and exercise stimulus required can be quite different.

How to know if that is your goal?

We often hear comments being made about body composition goals such as “I’m going to bulk up for next season” or “I could do with shedding a few pounds and leaning out”. However, more often than not, these statements are soon forgotten and not adhered to. It can be because someone doesn’t know where to start, what is required or isn’t quite committed to the process.

Gaining muscle is a long and slow journey, it requires a lot of patience and consistency. Let’s get a few things straight. If you are going to be successful in achieving a goal to build muscle, there are a few things you will need to expect:

- Progressive resistance training each week – consistently increasing the load

- Prioritise sleep – adequate sleep allows for recovery and adaptation

- Preparation to ensure you hit specific nutrient needs, carbohydrate, protein and healthy fats

- Hitting protein targets each day as well as the quality and timing of protein intake

- A consistent calorie surplus to build new mass

- Nutrient timing – pre and post workout

- Increase in fat mass

- Active recovery between sessions

- Prioritising the management of mental stress

What is a realistic goal for muscle building?

The amount of muscle mass a person can build will depend on many factors, such as their age, training history, training age, gender, health status, other training demands, mental health and stress management, available equipment and ability to progressively overload the muscles each week.

If you find that you are not gaining muscle mass, here are a list of potential reasons:

- You are not following an appropriate progressive overload resistance program

- You are not consuming sufficient calories and macronutrients

- You are completing too much aerobic based training

- You are overtraining and not allowing sufficient recovery between sessions

- You are not consistent with your training and nutrition

- Your timeframe to achieve your goal is unsustainable

- You are under a high degree of mental stress

Variables of muscle development

To elaborate on above a little more, an endurance athlete or someone who regularly trains for sport ie. hurling, badminton, horse riding, may be exceptionally fit and strong in their sport, but this does not necessarily mean that they are well trained when it comes to resistance training. Therefore their resistance training history and training age will be quite low and their gains are likely to be quite significant in the initial phase (usually the first 4 weeks) of the resistance training program.

The reason that people with a history of strength training (longer training age) are seen to have slower gains is due to reduced signalling responses to resistance training because they are more adapted to that type of exercise (also referred to as response plasticity). This adaptation makes it more difficult to increase strength and muscle size in comparison to an individual with no prior history of resistance training (Peterson et al., 2005, Coffey et al., 2006). Hence why those who are new to resistance training, will see more significant gains in the initial phase (usually the first 4 weeks) before the progress begins to plateau with greater adaptations to training stimulus. Research shows that greater gains are also achieved with higher training volumes (Schoenfeld et a., 2019). Therefore it is important that the volume progressively increases in order for the muscles to be consistently put under a greater amount of stress.

Research has also shown us that younger individuals find it easier to gain muscle mass with less fat mass accumulation, in comparison to middle aged and old age individuals.

Gender can also influence gains from a resistance training program. Men tend to be stronger relative to their lean body mass, particularly in upper body strength, and have larger muscle fibres in comparison to women, resulting in more significant gains (Miller et al., 1993). However gains relative to a person’s body size are generally similar.

Other sports and training demands on a person’s body can impact muscle gains on a training program as well. Where a person is training for strength and endurance, this is referred to as concurrent training (Wilson et al., 2012, Leveritt et al., 1999). Endurance training can limit increases in muscle size and strength from resistance training for various reasons. One being that different signalling pathways are activated from endurance and resistance training, and another being the risk of over training where there is a significant amount of muscle damage and the body struggles to recover adequately from (also referred to as non-functional overreaching or overtraining). We often see this where there are repeated frequent high-volume or high-intensity training sessions with inadequate recovery between them (Wilson et al., 2012, Hawley, 2009, Leveritt et al., 1999).

Those who are under a high degree of mental stress for example from work or relationships, or mental health issues, may find it more difficult to gain lean mass for a number of reasons. Firstly, if the body is in a constant state of stress, it will be next to impossible to recover between sessions in order to perform consistently over weeks and months. Other reasons can include:

- Suboptimal immune function and frequent illness

- Reduced appetite – not meeting energy and macronutrient requirements

- More prone to injury

- Growth hormone suppression

- Hormone dysfunction

- Burnout

- Resistance training & optimum nutrition is not a priority

- Inadequate or low quality sleep – leading to lower motivation to train and eat well

Progressive Overload

Progressive overload put simply means to continuously increase the load put on the muscles as they adapt and become bigger and stronger. Without increasing the load, the muscles will adapt and gains will plateau. If you have followed a resistance training program before, you will recognise that the same sets and reps that were once difficult to complete, are now less of a challenge. The load should be increased each week but no more than 10% to allow for gradual, progressive adaptation and avoid overtraining and injury. The increased stress you are placing on the muscles each week, will cause damage to the muscle fibres and force them to break down and repair, becoming bigger and stronger as a result. This is where your nutrition comes in, having adequate protein and energy on board, and at the right times, will support your muscles as they repair and adapt to the training stimulus. If you are looking to gain muscle mass, it is important that you follow a training program that takes this into account. Consult with a Strength and Conditioning coach and qualified performance nutritionist to develop your plan.

Setting your calories and identifying your approach

Firstly you have got to decide a few things and be honest with yourself:

- How much muscle do you want to gain?

- How quickly do you want to gain it?

- What is your training history like?

- What is realistic for you at this time?

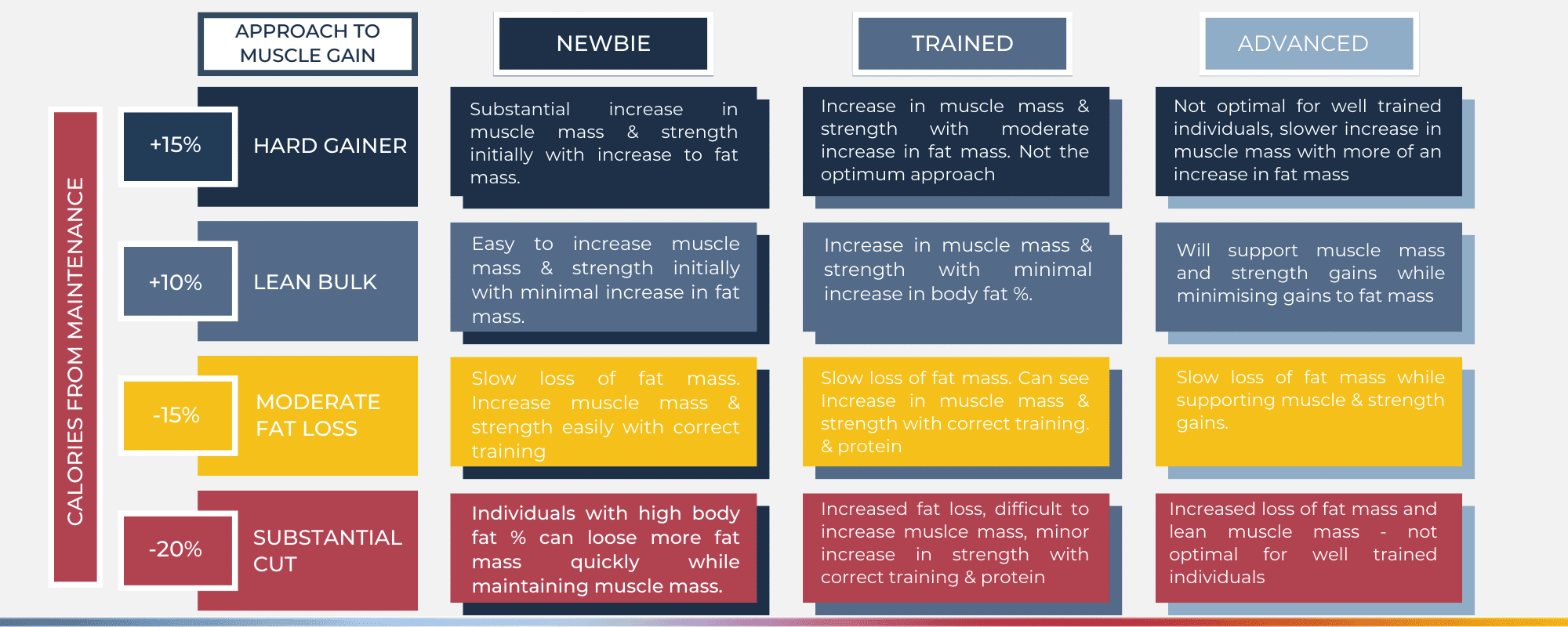

The amount of muscle the average person can expect to gain, with the correct training program and nutrition strategy is 0.3-0.4kg per week or about 1-2 kg per month. For the average individual, this would be an increase of 0.25-0.50% of current body weight per week can be expected where calories are increased by 10-20% above maintenance (Slater et al., 2019). However if you are highly resistance trained or have a considerable amount of muscle mass already (ie. close to your genetic limit) the gains are likely to be slower and less substantial.

What are you leaving on the table?

A more dramatic increase in calories will lead to more efficient gains in muscle mass, along with an increase in fat mass. Which approach to building muscle that you should implement will be individual to you. If you have a longer history of resistance training and longer time available to reach your goal, you may opt for a less dramatic calorie surplus. This will lead to a slower increase in muscle mass with less accumulation of fat mass. For someone who struggles to gain weight and wants to increase muscle mass faster, a more substantial calorie surplus will be more effective, though is likely to involve more of an increase in fat mass. To summarise, the more calories you consume, the more muscle and fat you are likely to gain, and the less calories you consume, the less muscle and fat mass you can expect to gain.

Maybe muscle building isn’t for you?

Therefore if you are going through a period of intense stress in your life or you are aware that you are not managing your stress very well, perhaps a muscle building goal isn’t right for you at this time. Building muscle requires putting the body under considerable physical stress and a consistent lifestyle routine to support recovery and performance, week in, week out. If you are not prepared for this or in a position to support your recovery, it is likely that you will not achieve your goal and furthermore, you will put yourself under more undue mental and physical stress in the process.

If this sounds like you, I suggest making your health and stress management a priority. Focus on building a consistent routine around your nutrition, sleep and exercise. Make your mental health a priority by practising meditation, yoga, speaking to someone you trust or a professional such as your GP or a psychologist. If you are struggling with your nutrition and determining what your goal is I would encourage you to book a 1-1 consultation with an experienced nutritionist. Together you can identify and define your goal to develop a plan that suits your needs at this time. You can contact us at heather@daveynutrition.com.

So, what should I eat to build muscle?

- Have a performance training plan that is personalised to your needs; use the daveynutrition performance calculator to make sure you have a clear understanding of your daily energy and nutrient needs.

- Follow a daveynutrition meal plan that matches your nutrient needs from the meal plan section.

- Eat a fast-digesting CHO source coupled with a quality source of protein post-workout (0.8 g of CHO per kg BM and 0.3 g of protein per kg BM). This amounts to at least 20 g of protein for most people.

- Consume at least 3 g CHO per kg BM daily, primarily before and after your exercise session

- Larger volumes of CHO (4-6g per kg BM) should be ingested if general physical activity or indeed training intensity and volume is notably high such as after interval sessions > 60 minutes.

- Consume at least 1.7-2.0 g of protein per kg BM daily.

- Consume adequate amounts of essential fats from avocados, fish, fish oils, walnuts, pecan nuts and flaxseed.

- Aim to create a calorie surplus of roughly 300-500 kcal on a daily basis from nutritious food sources.

- If you are meeting all your nutrition needs and following a well-structured training program, you could also consider creatine supplementation to support the development of muscle mass. For more details on creatine supplementation read our article here.

- If you are struggling with your goal of gaining muscle and would like more guidance, why not book in for a consultation with one of our nutritionists? Email heather@daveynutrition.com to learn more about our services.

References:

Schoenfeld, B. J., Contreras, B., Krieger, J., Grgic, J., Delcastillo, K., Belliard, R., & Alto, A. (2019). Resistance Training Volume Enhances Muscle Hypertrophy but Not Strength in Trained Men. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 51(1), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001764

Coffey, V. G., Zhong, Z., Shield, A., Canny, B. J., Chibalin, A. V., Zierath, J. R., & Hawley, J. A. (2006). Early signaling responses to divergent exercise stimuli in skeletal muscle from well-trained humans. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 20(1), 190–192. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.05-4809fje

Peterson, M. D., Rhea, M. R., & Alvar, B. A. (2005). Applications of the dose-response for muscular strength development: a review of meta-analytic efficacy and reliability for designing training prescription. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 19(4), 950–958. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-16874.1

Miller, A. E., MacDougall, J. D., Tarnopolsky, M. A., & Sale, D. G. (1993). Gender differences in strength and muscle fiber characteristics. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology, 66(3), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00235103

Hawley JA. Molecular responses to strength and endurance training: Are they incompatible? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 34: 355–361, 2009.

Leveritt M, Abernethy PJ, Barry BK, Logan PA. Concurrent strength and endurance training. A review. Sports Med 28: 413–427, 1999.

Wilson, J. M., Marin, P. J., Rhea, M. R., Wilson, S. M., Loenneke, J. P., & Anderson, J. C. (2012). Concurrent training: a meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 26(8), 2293–2307. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3e2d